This painting occupies an extremely important place in the body of David's work and

in the history of French painting. The story was taken from Titus-Livy. We are in the

period of the wars between Rome and Alba, in 669 B.C. It has been decided that the

dispute between the two cities must be settled by an unusual form of combat to be

fought by two groups of three champions each. The two groups are the three Horatii

brothers and the three Curiatii brothers. The drama lay in the fact that one of the

sisters of the Curiatii, Sabina, is married to one of the Horatii, while one of the sisters

of the Horatii, Camilla, is betrothed to one of the Curiatii. Despite the ties between

the two families, the Horatii's father exhorts his sons to fight the Curiatii and they

obey, despite the lamentations of the women.

David succeeded in ennobling these passions and transforming these virtues into

something sublime. Thus had Corneille and Poussin also done. Moreover, David

himself stated: "If I owe my subject to Corneille, I owe my painting to Poussin."

However, unlike Corneille, David finally decided to treat the beginning, rather

than the denouement of the action, seeing that initial moment as being charged with

greater intensity and imbued with more grandeur. And, it was he who chose the idea

of the oath (it is not mentioned in the historical accounts), transforming the event

into a solemn act that bound the wills of different individuals in a single, creative

gesture. He was not the first painter to do so, but certainly the first to do it in such a

stirring manner.

If he was thus paying homage to the spirit of Poussin, from whose Rape of the

Sabine Women he also borrowed the figure of the lictor for his drawing of the youngest

Horatius, his conception was nonetheless much more sober and innovative. Instead of following

a tight order, David disposed the figures in a spacious and

rhythmical series. They stand out against something that resembles not so much an

antique-style frieze as a three-dimensional proscenium, forcefully asserting their

autonomy.

In addition, the viewer's eye is spontaneously able to grasp only two superimposed orders- that

of the figures and that of the decor. The first is striking because it

is organized into three different groups, each with a different purpose. To the appeal

of the elder Horatius in the center, the reply on the left is the spontaneous vigor of the

oath, upheld loudly and with a show of strength, while on the right it is a tearful

anguish, movement turned in upon itself, compressed into emotion. The distance between the

figures accentuates this contrast. To the heroic determination of the men

the canvas opposes the devastated grief of the women and the troubled innocence of

the children.

The decor is reduced to a more abstract order, that of architectural space- massive columns,

equally massive arches, opening out onto a majestic shadow. The three

archways loosely correspond to the three groups.

The contemplative atmosphere is softened by shades of green, brown, pink, and

red, all very discreet. Instead of opening his painting out onto a landscape or an expanse of sky,

David closes it off to the outside, bathes it in shadow. As a result, the

light in this setting takes on a brick-toned reflection, which encircles his figures with

a mysterious halo.

Through David's rigorous and efficient arrangement, the superior harmony of

the colors, and the spiritual density of the figures, this sacrifice, transfigured by the oath, becomes the founding act of a new aesthetic and moral order.

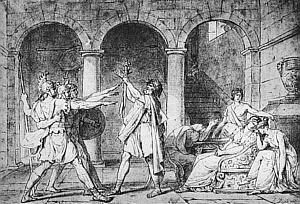

Study for: "The Oath of the Horatii", 1782, pen and black ink with gray wash and highlights of white over black pencil, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lille.

|

Return to J. L. David page